Consumer organization and operating models for the next normal

Many consumer-goods companies and retailers have risen to the challenges presented by the pandemic. Seven core practices can help them keep what has worked and prepare for what lies ahead

The COVID-19 pandemic is posing staggering health and humanitarian challenges. As the crisis evolves, companies must act on multiple fronts to protect their employees, customers, supply chains, and financial performance. Retail and consumer goods sectors have been particularly affected, with frontline employees directly at risk and companies struggling with the demand that is either rapidly evaporating or surging well past the available supply.

These most trying of circumstances have forced organizations to adapt quickly. In the process, many have achieved what they had aspired but failed to deliver for years. Decisions are made faster. Innovation cycles have dropped from months to days. Working remotely, previously a benefit offered to a portion of workers at some companies, is now an imperative for most employees. Companies are putting a greater emphasis on employees’ physical and mental health than ever before, and they’re celebrating leadership capabilities that weren’t considered critical before the crisis.

These shifts occurred out of necessity—and, without thoughtful action, many of the recent changes are likely to revert over time to more traditional approaches. Leading companies will use this moment as an opportunity to rethink and reset their operating models for the future.

The seven shifts of the next normal

As companies reconsider and reconfigure their operating models, they need to be sure to underpin them with seven core practices that will define the next normal1 (Exhibit 1).

1. Reset of operating model and rhythm based on fewer (and bigger) priorities

In the past few weeks, we have seen a sharper focus on top priorities, while less critical initiatives have been paused or discontinued altogether. A recent McKinsey survey of more than 100 executives at consumer organizations2 revealed a desire for this sharpened prioritizing to continue and permeate into the next normal. As the fight-or-flight instincts triggered by the crisis relax, companies will be tempted to return to more familiar modes of employee engagement.

Sustaining the type of focus and strategic clarity we see today will require deliberate process changes and leadership commitment. The most focused companies use a variety of practices to align their organizations with a clear set of priorities. One such practice is having disciplined management meetings, including structuring the executive-team calendar to explicitly support strategic priorities. Organizations are also establishing working norms that ensure the management team’s time together is focused on major decisions, avoiding tactical discussions, and leaving ample time to ensure team alignment with company priorities.

Most companies also find that frequently—and formally—revisiting strategic priorities, a necessity during the COVID-19 crisis, is beneficial. This review can take the form of quarterly executive-team check-ins to assess existing initiatives and to determine whether to accelerate, evolve, or stop them or to address more structural elements, such as shifting from a three-year strategic-planning process to a more dynamic resource-allocation model.

Finally, aligning with fewer (and bigger) priorities may also enable an organization to reset organizational and operating structures. Narrowing down priorities can afford organizations a chance to realign their business segments with the top priorities, rather than with more traditional category or geographic segments, by elevating key brands, countries, or information to the CEO in a much more deliberate way. Moreover, it may allow the senior leadership team to incorporate new roles, both permanent and temporary, that reflect the new priorities: M&A, business building, and transformation.

2. Comprehensive cost reset

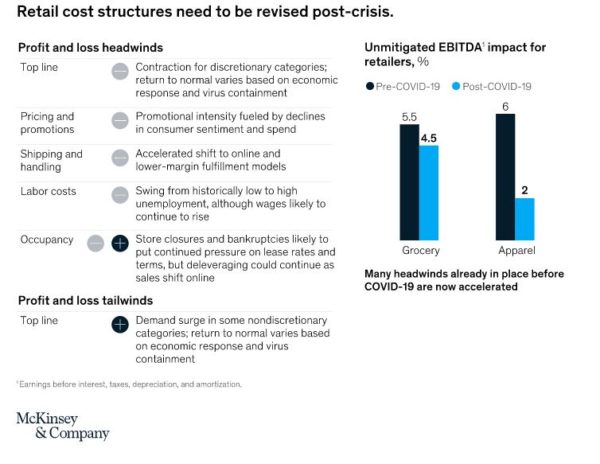

To recapture pre-COVID-19 margins, many consumer-facing organizations will need to reset their cost structures (Exhibit 2). Disrupted categories (for example, white goods and apparel) are suffering, but even surge categories such as grocery will be adversely affected in the long term because of shifting consumer sentiment and models of consumer interaction, such as curbside pickup.

Our preliminary impact assessment found that retailers that don’t proactively adapt to changing conditions could see their margins fall 200 to 400 basis points because of increased labor and fulfillment costs. The short- to the medium-term impact of shifts in costs and revenues is equivalent to 20 to 30 percent of general and administrative costs. This reduction doesn’t include the additional investment necessary to build capabilities that will enable growth.

The story for consumer-goods companies is more nuanced; some categories have flourished thanks to near-term stock-ups while other, more discretionary consumer goods have been affected adversely. Although the margin implications will vary by subsector, the need to invest in new and emerging capabilities, such as digital, data, and analytics (DD&A), is universal. Focused priorities and streamlined decision making naturally create an opportunity to reset the cost structure.

Cost resets are known commodities to most established organizations, but the coronavirus offers a twist on the traditional approach. Physical footprints will change to accommodate people coming back to work. Physical-distancing protocols will likely need to be put in place, at least in the near term, to make sure that employees feel safe. New flexible work options will have immense HR and IT implications. These and other changes will compel companies to adapt their organizational structures and operating models.

3. Significant resource distortion to must-win capabilities

Many of the shifts in recent months represent a substantial acceleration of consumer trends that had already been in progress for some time. For instance, online shopping is up by 20 to 70 percent since the pandemic began, and supply chains are adapting rapidly. Store economics have been strained for some time, and we expect store footprints to continue to shrink. In the next normal, many stores could become nodes in a retailer’s supply chain. These stores could also increasingly reflect the tastes of local consumers as they adapt the product, pricing, and promotions to each market. Finally, the international spread of the coronavirus has accelerated the premium on flexibility in supply chains, including in partner terms and sourcing (particularly nearshoring).

We have observed other shifts that are much newer but likely to be similarly long-lasting. For example, the unprecedented focus on hygiene during the crisis has prompted updated hygiene protocols and a rise in single-use plastics and wipes. These changes are having an impact on sustainability and are forcing companies to innovate eco-friendly alternatives. Physical-distancing protocols also have prompted a rush to adopt contact-free payment and fulfillment models: about 30 percent of consumers intend to continue using self-checkouts after the crisis, and companies have innovated new delivery and pickup models. The final, but perhaps most troubling, the shift is a shock to customer loyalty. Up to 40 percent of consumers have switched stores and brands during the crisis, and many may choose to keep their new habits.

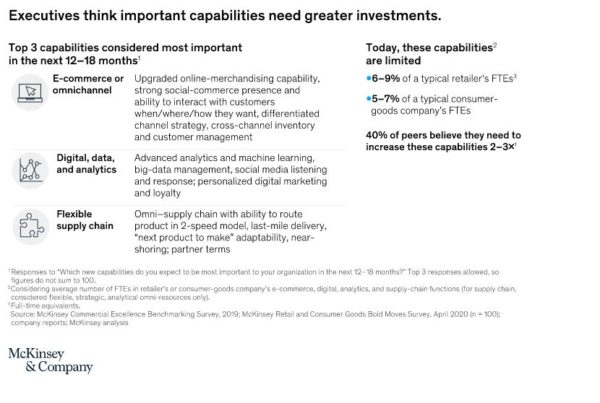

Retailers and consumer-goods companies should ensure that they are strategically positioned to capture growth from these significant trends. Doing so may require investing further in existing capabilities such as e-commerce or innovation or in a new set of capabilities—for example, flexible supply chains, omnichannel sales capabilities, and more accelerated DD&A. It may also include rethinking marketing strategy, capabilities, and spending to better engage with changing consumer sentiments and habits. Organizations may consider pursuing M&A to rapidly gain priority capabilities: the environment is changing quickly, and winners will be out in front.

An average retailer allocates about 6 to 9 percent of its total resources to e-commerce, DD&A, and flexible supply chains. In consumer packaged goods, the number is similar—about 5 to 7 percent of resources. However, according to our recent survey of retailers and consumer companies,3 respondents believe they will need to allocate two to three times more than their current level of resources to increase these capabilities in the future (Exhibit 3).

4. Acceleration to the flexible workforce of the future

The COVID-19 crisis has dramatically increased experimentation with flexible workforce models. The use of video-conference applications has risen by a factor of five to seven, and organizations have become more adept at working remotely. Talent exchanges are being created to address the imbalances between labor supply and demand by, for example, connecting disrupted retailers and consumer-goods organizations that have furloughed or laid off employees with companies that are looking to hire workers quickly. One such exchange, powered by Eightfold.ai and FMI, was launched in early April and, within just two weeks, listed more than 600,000 job openings in the food industry. Some companies have internal talent exchanges: one Chinese cosmetics retailer used one to reposition its store workers to be online influencers.

In the longer term, we will likely see two major developments. First, a so-called talent-anywhere strategy, with teams consisting of members across locations, could become increasingly common and allow employers to strengthen capabilities in geographies where they have been difficult to build. For example, we mapped the population of data scientists across the United States and found that nearly 70 percent of the headquarters for the top 100 retailers and top 100 consumer-goods companies were more than 50 miles from the nine largest concentrations of data scientists (Exhibit 4).

Second, to load-balance peaks and troughs, new talent marketplaces will emerge across functions to enable labor sharing by companies that don’t compete with one another. This development may also establish a more standardized “certification” among retailers and consumer-goods companies for some common roles (such as cashier, stocker, line manager, and distribution coordinator), potentially reducing the talent-recruitment burden for HR.

Last, the increased use of the gig economy for specialized labor, such as designers, could reduce the need for in-house niche expertise or large centers of excellence. Many retailers, for example, are rethinking their large in-house creative agencies.

5. Changed employee value proposition

The COVID-19 crisis has changed the employer-employee dynamic. Recent events focused both parties on employee benefits (for example, health insurance and sick leave), protective measures (such as personal protective equipment), and the new norm of remote working.

While this focus will, with time, recede, it is possible that consumer expectations for how employees treat their talent will remain altered. Existing safety protocols may be expanded as personal protective equipment becomes table stakes for many roles. Employees shocked by the high and rising unemployment rate will look for employers to provide opportunities for them to retrain in a lost-cost, online way. Employees in critical roles may be well-positioned to demand that the expanded benefits they were offered during the crisis lockdown (for example, more generous sick-leave policies and enhanced medical benefits) be maintained.

That said, these benefits and improved working conditions come at a price—and most consumer companies will be keeping a close eye on their sales, general, and administrative costs over the coming months, if not years. The acceleration to a more flexible workforce may generate efficiencies that enable this changing dynamic.

6. Sustained metabolic rate of decision making

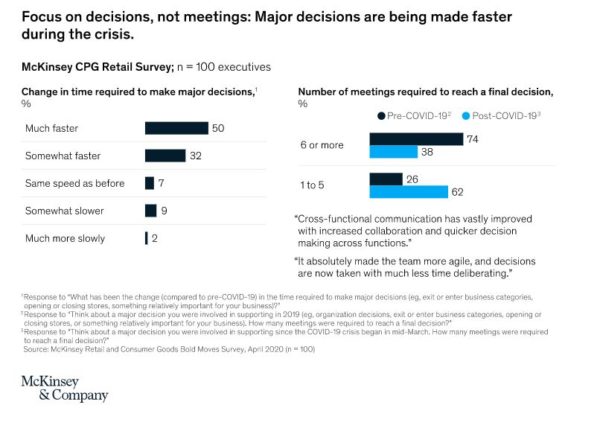

We have also noted the emergence of expedited and more focused decision making across consumer organizations. In our survey, more than 80 percent of executives said that decisions during the COVID-19 crisis are being made faster than before the crisis. Respondents also revealed that major decisions, such as closing stores or exiting a business unit, are requiring far fewer meetings: almost two-thirds require five meetings or fewer compared with one-quarter before the crisis (Exhibit 5).

While the need for accelerated decision making is obvious during this trying time, the ability to sustain such speed is something that companies have struggled with for years. In addition to determining the right governance to continue to make decisions at pace, companies must also establish the infrastructure to communicate and implement them in a thoughtful way.

One way to help maintain this practice is by categorizing decisions and speeding up those that need to be made quickly and paying more attention to those that matter most or need careful handling. Some leading companies determine the level of impact (positive or negative) at stake and the frequency each decision is made (and therefore the familiarity of the decision). With this approach, organizations can delegate lower-impact decisions, which often accelerates their execution, and focus leadership time on the big bets, which frequently require time-consuming, cross-functional coordination.

Another approach is to think about how to build a minimal viable product (MVP) for different types of decisions. Many companies have done this throughout the crisis without even realizing that they were doing it. Retailers have focused on MVPs for store reopenings, and consumer-goods companies have replanned and rebudgeted the year (which normally takes weeks or months) in days.

Using both a decision framework and an MVP mindset will help consumer organizations to sustain the metabolic rate and speed of decision making they have had during the crisis.

7. Heightened focus on leadership development

The crucible of COVID-19 is highlighting leaders who are stepping up in new ways—as well as revealing unexpected gaps in leadership. In these extraordinary times, an intuitive leader may often be more effective than a tenured one, since reliance on experience and traditional skills may be insufficient. The best leaders can:

- be empathetic—and open to empathy in return

- shift their management style to enable instead of “command and control”

- demonstrate decisiveness amid uncertainty

- be a role model of deliberate calm and bounded optimism

As companies restart and settle into the next normal, they should aim to create more opportunities for leaders to make rapid, high-stakes, and cross-functional decisions as part of the normal operating model. Organizations should identify individuals in their leadership pipeline who may fall short in the next-normal operating model. Should any succession plans be reconsidered in light of COVID-19? How could leaders benefit from peer-to-peer coaching?

Putting it all together

When all of these trends are viewed together, it’s clear that this crisis has required, and will continue to require, companies to make big and bold changes. The recent pace and depth of change have demonstrated what’s possible; companies will need to continue to push beyond the way things have been done in the past, but first, they must cement the positive changes they have made since the onset of the pandemic.

By restructuring their organization to focus on the newly created priorities, modernizing their operating models to account for remote working and faster decision making, and shifting routines and rituals to bring value to shareholders, customers, and employees, leading companies will find ways to emerge from the COVID-19 crisis stronger than they were before. Such opportunities do not present themselves often, and organizational leaders need to act now to prepare for the next normal–which, before we know it, we’ll all be living in.

This article was written collaboratively by the McKinsey Consumer Goods and Organization Practices, groups that span all of our regions and include: Ayush Agnihotri, Bryan Logan, Kristi Weaver, Oren Eizenman, Kate Lloyd George, and Lauren Ratner.